What is sparkling prose?

Let's investigate commonly used phrases in book reviews and literary discourse. Up first: what is sparkling prose?

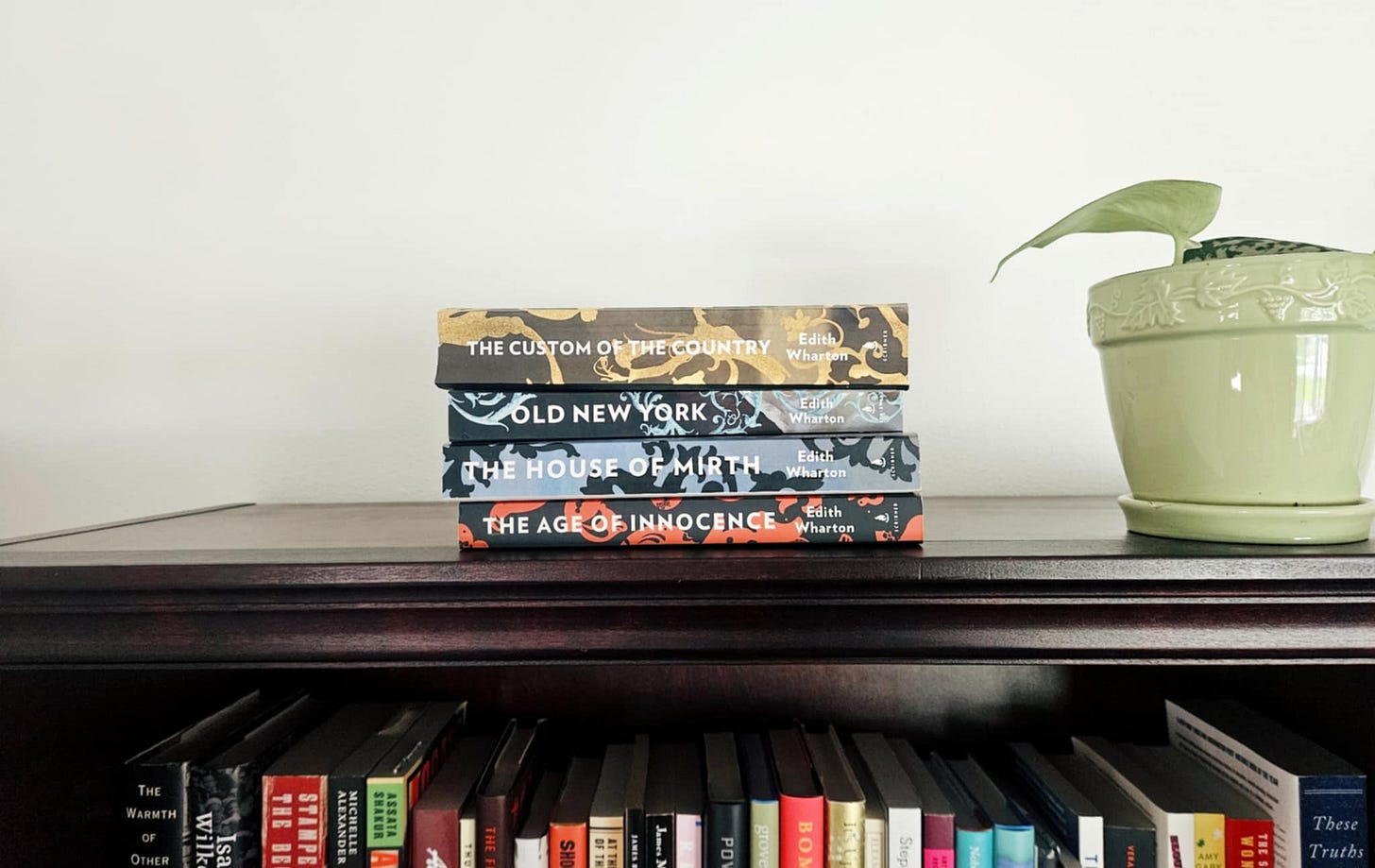

Last month, I spotted two Substack Notes praising Edith Wharton and Jane Austen’s sparkling prose. These two authors are top of mind as I contemplate a short Wharton project and wrap up our Emma readalong for Novel Pairings, so these back-to-back references stopped my scroll. Although Wharton and Austen both write about class, marriage, and social irony, their writing styles feel distinct to me. And yet, I can see how both authors earn the sparkling prose descriptor.

What is sparkling prose?

Whereas poetry deliberately uses rhythm, rhyme, or meter to convey meaning, prose gets closer to natural speech patterns. Prose is more conversational, but even conversations contain their own rhythm and style. Authors use diction, tone, syntax, and figurative language in order to create variations under the prose umbrella. For instance, if you enjoy “poetic prose,” you gravitate towards writing peppered with metaphor, sensory details, and sentences that beg to be read aloud.

To define sparkling prose, think of someone with a “sparkling personality.” They light up a room. They are quick-witted and quick to laugh. Their laugh might even be musical, contagious. They catch attention in a conversation. They entertain.

Sparkling prose creates the same attention-grabbing personality on the page with lively, vivid, and tangible details. For example:

Edith Wharton opens The Custom of the Country with a colorful description of the Hotel Stentorian. It is easy to picture this as a room for strivers, with its ornate decor and royal portraits, but it is also just easy to picture the room.

Mrs. Spragg and her visitor were enthroned in two heavy gilt armchairs in one of the private drawing-rooms…The Spragg rooms were known as one of the Looey suites, and the drawing-room walls, above their wainscoting of highly-varnished mahogany, were hung with salmon-pink damask and adorned with oval portraits of Marie Antoinette and the Princess de Lambelle.

More impressively, she captures her characters with specificity and physical descriptions that double as interior characterization. When you meet these people in their setting, you immediately know them, not just what they look like.

Mrs. Spragg herself wore an air of detachment as if she had been a wax figure in a show-window. Her attire was fashionable enough to justify such a post, and her pale soft-cheeked face, with puffy eye-lids, and drooping mouth, suggested a partially-melted was figure which had run to double-chin.

[Undine Spragg] was always doubling and twisting on herself, and every movement she made seemed to start at the nape of her neck, just below the lifted roll of reddish-gold hair, and flow without a break through her whole slim length to the tips of her fingers and the points of her slender restless feet.

Sparkling prose often contains humor or a sassy spirit (especially in dialogue).

While reading Austen, I can almost imagine the twinkle in her eye as she wrote dialogue such as:

“Mr. Bennet, how can you abuse your own children in such a way? You take delight in vexing me. You have no compassion for my poor nerves.”

“You mistake me, my dear. I have a high respect for your nerves. They are my old friends. I have heard you mention them with consideration these last twenty years at least.”

Sparkling prose moves quickly. It does not bog a reader down.

Reading Austen or Wharton may not feel exactly like reading contemporary literature, but their prose does feel lighter than something like Mary Shelley’s gothic seriousness. Compared to Shelley, the snippets above feel zippy and spry, light on their feet. For contrast, read this sample from Frankenstein:

Even broken in spirit as he is, no one can feel more deeply than he does the beauties of nature. The starry sky, the sea, and every sight afforded by these wonderful regions, seems still to have the power of elevating his soul from earth. Such a man has a double existence: he may suffer misery, and be overwhelmed by disappointments; yet, when he has retired into himself, he will be like a celestial spirit that has a halo around him, within whose circle no grief or folly ventures.

I suspect sparkling prose has a lot to do with setting, too.

A few years ago, Larry McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove surprised me with its vivid setting, humorous dialogue, and page-turning plot. It’s hard to think of a book set in the dusty Old West as “sparkling,” even though I think Larry McMurtry’s prose actually fits most of the requirements above!

I’m not sure you can have sparkling prose without a champagne-and-chandeliers setting. Americans associate Gilded Age or the Roaring Twenties with opulence, glittering parties, and elaborate costumes. Hollywood creates the same sheen on the Regency period of Jane Austen with pretty dresses, candlelight casting a glow over country dances, and romantic declarations of love. For Wharton, Austen, and other authors in these time periods, the setting is sparkling, and the prose is lively.

Aside from indulging my Big English Teacher Energy, why bother with this definition?

Like most internet communities, book enthusiasts have their own shorthand. I’m less familiar with the BookTok lexicon, but after nearly a decade on Bookstagram, I don’t question what a reader means when they say a book “didn’t live up to the hype” or (my personal pet peeve) “the second half fell flat for me.”

Professional book reviewers also draw from a common vocabulary. We’ve all come across a reviewer who was captivated by a “stunning debut” that was a real “tour de force” with its “lyrical prose” and “tightly plotted” narrative.

It’s natural for any subculture to adopt consistent lingo, and it’s a good thing! Language evolves and contributes to a sense of community. One phrase can communicate a lot in just a few words. But certain phrases can also flatten book reviews or confuse readers who aren’t “in the know.”

I would love to improve online book discourse by being more specific. I’m also a word nerd, which is where this series comes in. Let’s investigate common words and phrases from bookish vocabulary, just like I did with “sparkling prose” today. (I’ve been working on a piece about books “falling flat” for a while now.)

If you have a word or phrase to recommend for a future installment, please let me know! I would love to hear from you on this topic. You can use this form, send me a Substack message, or leave a comment to reach me.

How would you define sparkling prose? Can you think of contemporary examples?

The first contemporary book that comes to my mind with “sparkling prose” is On Beauty by Zadie Smith. What do you think?

P.S. In case you missed it, I re-introduced myself by way of my favorite books.

Meet me at the bookshelf

Hey, readers! As I get back into the routine of regular newsletter writing, I think I’m due for a reintroduction. Instead of a brief biography, how about meeting me through some of my favorite books?

Love this idea for a series!

Catalina a short novel I LOVED got described as a “sparkling debut” by the NYT. I didn’t really understand what they meant, because the book is wild and wonderfully unhinged but I think I get what they were going for now.